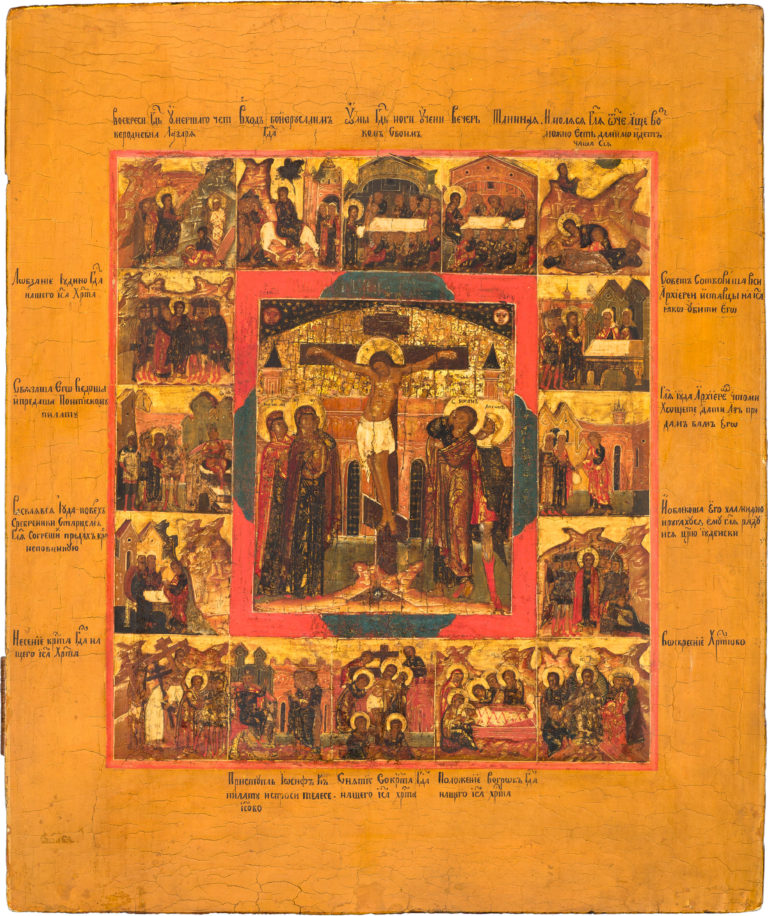

The Crucifixion, with the Passions of Christ and Church Feasts in 16 Border Scenes

Centerpiece of the religious icon: around the middle of the 17th century. Volga region (possibly Yaroslavl).

Borders of the religious icon: 19th-century antique restoration.

Size: 40 х 33.5 х 3 cm

Wood (one whole board), two incut support boards, a shallow incut centerpiece, canvas not visible, gesso, tempera.

The author’s paintwork is in a satisfactory state, partially chafed. There are also numerous small fallouts of gesso and paint. The given hand-painted Orthodox icon went through ‘antique restoration’ in the 19th century; paintwork on the borders was completely restored, partially afflicting the border scenes. The gold background, halos of the saints, and the gold graphics of the vestments were also redone in this period.

Contact us

The Crucifixion, with the Passions of Christ and Church Feasts in 16 Border Scenes

Diagram of the border scenes:

Diagram of the border scenes:

- The Raising of Lazarus;

- The Entrance into Jerusalem;

- The Washing of the Feet;

- The Last Supper;

- The Prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane;

- The Betrayal of Judas;

- The Bringing of Christ before Caiaphas;

- The Bringing of Christ before Pilate;

- Judas receives the 30 pieces of silver;

- Judas repents and returns the blood money;

- The Mockery of Jesus;

- The Carrying of the Christ;

- Joseph asks Pilate for the body of Christ;

- The Taking Down of Jesus from the Cross;

- The Entombment of Christ;

- The Resurrection – The Harrowing of Hades.

This hand-painted Orthodox icon represents a rare example of religious icon paintings depicting the last days of Christ, His burial, and Resurrection.

The Suffering and Death of the Lord Jesus is described in all four Gospels (Mathew. 27:33–38; Mark. 15:22–27; Luke. 23:33–43; John. 19:17–25), as well as in numerous apocryphal sources. The iconography of the Crucifixion scene in the centerpiece of this antique Russian icon is traditional, shortened version of the scene known from the 14th century; it includes only a small number of those present. Besides the Crucified Jesus, the composition includes the Mother of God in the dark-red maphorion, Mary Magdalene in the bright cinnabar robes, the lamenting John the Theologian, and Longinus the Centurion. The scene unravels before the walls of Jerusalem – executed in a rather symbolic way and crowned with two towers. The Cross is placed on a mountain, below which we see a cave, where lies the skull of Adam. According to Church tradition, Adam was buried on Golgotha, and the Blood of Christ touched his skull washing the Original sin and, therefore, allowing mankind to enter Eternal Life. The symbolic depictions of the Sun and Moon surrounding the cross are directly linked with the Gospel narrative, according to which, at the moment of Christ’s death, the Sun went dark and the Veil in the Temple was town in two (Luke 23, 44-45). “They bound Christ – the Sun, yet He broke the eternal bonds, and brought light to the dark places, and defeated the devil. The Sun came under the Earth, and darkness covered the Jews” (“The Word…” of St. Epiphanius of Cyprus). The scenes that surround the centerpiece of this Russian Orthodox icon of Christ bear the detailed description of His last days and burial. Yet the iconographic scheme brings its theological complexity, starting the narrative with the Raising of Lazarus, which is seen as a crucial forerunning event of the Resurrection and God’s Salvation of Mankind.

The artistic traits of the published antique Russian icon – ‘miniature’ painting style, the subtle color scheme (which combines various shades of ochre, brown, and green with bright cinnabar and white accents), the soft modeling of the faces over the brown sankir (with a touch of gentle sanguine), the colorful mountains with small lights – find very close analogies in the 17th century Russian Eastern Orthodox iconography and allow this hand-painted icon to be attributed to the work of a Volga-region master, possibly hailing from Yaroslavl. The fact that the given antique Russian icon was held by the Old Believers is attested to the delicate restoration executed in the 19th century by an unknown religious icon master. The Passion theme was especially popular with the Old Believers, who read detailed poetical and theological treatises on the suffering of Christ during Passion week, preferring them over the Gospel narratives.