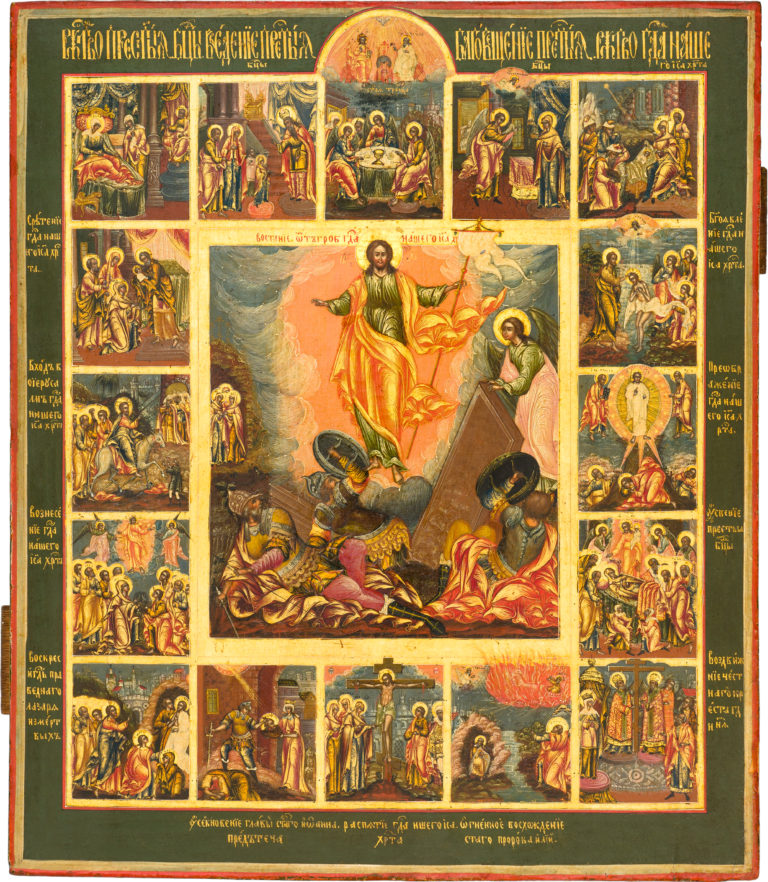

The Resurrection, with Church Feasts and the Holy Trinity in 16 Border Scenes

Antique Russian icon. End of the 18th century. Yaroslavl

Size: 36 х 30.5 х 2.1 cm

Wood (one whole panel), two incut profiled support boards, absence of an incut centerpiece, underlying layer of canvas not visible, gesso, tempera, gold.

The author’s paintwork is in a very good state. Slight chafing and fallouts of paint.

The reverse of the antique icon panel bears several pencil inscriptions. Over the upper support board (in two lines): «Освящена 1го Апреля 1915го года / палеховскомъ Крестовоздвиженск. Храме» (Blessed April 1st, 1915/in Palekh’s Elevation of the Holy Cross Church). Under the upper support board (in the same handwriting): «Сей Образъ куп. 1915 года Марта 19го дня въ Москве» (This icon bought on March 19th, 1915 in Moscow). Bellow, in the center of the panel: «семья Сусловых» (The Suslov Family).

Contact us

The Resurrection, with Church Feasts and the Holy Trinity in 16 Border Scenes

Diagram of the border scenes:

- The Nativity of the Mother of God;

- The Entrance of the Mother of God into the Temple;

- The Old Testament Trinity;

- The Annunciation;

- The Nativity of Christ;

- Candlemas (The Meeting of Christ in the Temple);

- The Theophany (The Baptism of Christ);

- The Entrance into Jerusalem;

- The Transfiguration;

- The Ascension;

- The Dormition of the Mother of God;

- The Raising of Lazarus;

- The Beheading of John the Baptist;

- The Crucifixion;

- The Fiery Ascent of the Prophet Elias;

- The Elevation of the Holy Cross;

- The New Testament Trinity (The Enthronement).

Despite the fact that all Gospels tell of the Resurrection of Christ (Matthew. 28:1–20; Mark. 16:1–18; Luke. 24:1–49; John. 20:1–29), neither actually describes the event itself; it remains shrouded in mystery. Nevertheless, already in the Middle Ages, Russian icon artists embraced the ‘Rising from the Tomb’ scene, which was taken from Western European etchings. Such Russian icon paintings depict Christ – Risen from the Dead and Rising over a tomb, the lid of which is held by an Angel, while the frightened Roman warriors try to cover themselves with their shields, blinded by the radiant light. This version of the Resurrection religious icon paintings won its greatest popularity in the Imperial period, with various Western European etchings serving as samples. In the centerpiece of the given antique hand-painted icon, the Savior is depicted frontally, with arms spread bearing a standard, and wearing a tunic and a broad himation, which differs from the majority of “The Rising” scenes, where Christ is usually half naked.

The Eastern Orthodox iconography of the border scenes also bears strong Western orientation reworked in a traditionalist fashion. A unique iconographic trait is found in “The Dormition of the Mother of God.” In the scene of “The Miracle of Athonius,” we see a figure of an elderly man with his hands covered, while the Angel with the sword is entirely omitted. Since Imperial-period religious icon masters were often blindly dependent on the samples, it is quite possible that here we don’t see some special idea; rather, the artist was inattentive and made two depictions of Athonius, instead of one.

The masterful, exquisite artwork clearly indicates that this piece of hand-painted Orthodox icons is one of the great examples of Yaroslavl iconography. The hand of an unknown but first-class Yaroslavl religious icon artist is felt in a number of traits: the calligraphic precision of the graphic work, the compositional scheme, the selection of various foreshortenings, the extravagance of the paintwork, the brilliance of the narrative, and the extreme decorative spirit of the piece.

The white-toned faces with the bright rouge and the overall powerful and bright color scheme of the given antique Russian icon (which includes blues, greens, reds, and crimson rose tones) are typical for a series of famous religious icons of the 18th century and find analogies among the detailed compositions devised by Climent Mokrousov and Theodore Krasheninnikov.

The provenance of this beautiful hand-painted icon is linked with Moscow, where it was bought a century after its completion, in 1915 (as stated in the inscription). The Russian icon was blessed in the oldest church of Palekh – the Elevation of the Holy Cross. The owners, as indicated, were the Suslov family. There are several iconographers in Palekh are known to bear this name. It could have been Pavel Ivanovich Suslov (1877-1939), a portrait master iconographer working in the well-known Sofonov workshop, or Vasiliy Vasilievich Suslov, an academic, whose father Vasiliy Nikanorovich held an iconographic workshop in Moscow in the 19th century. It is possible that the bright-toned, virtuoso painting style – so favored by Palekh’s artists – drew the attention of the iconographers, who valued such historic pieces and brought together Eastern Orthodox icon collections of their own.