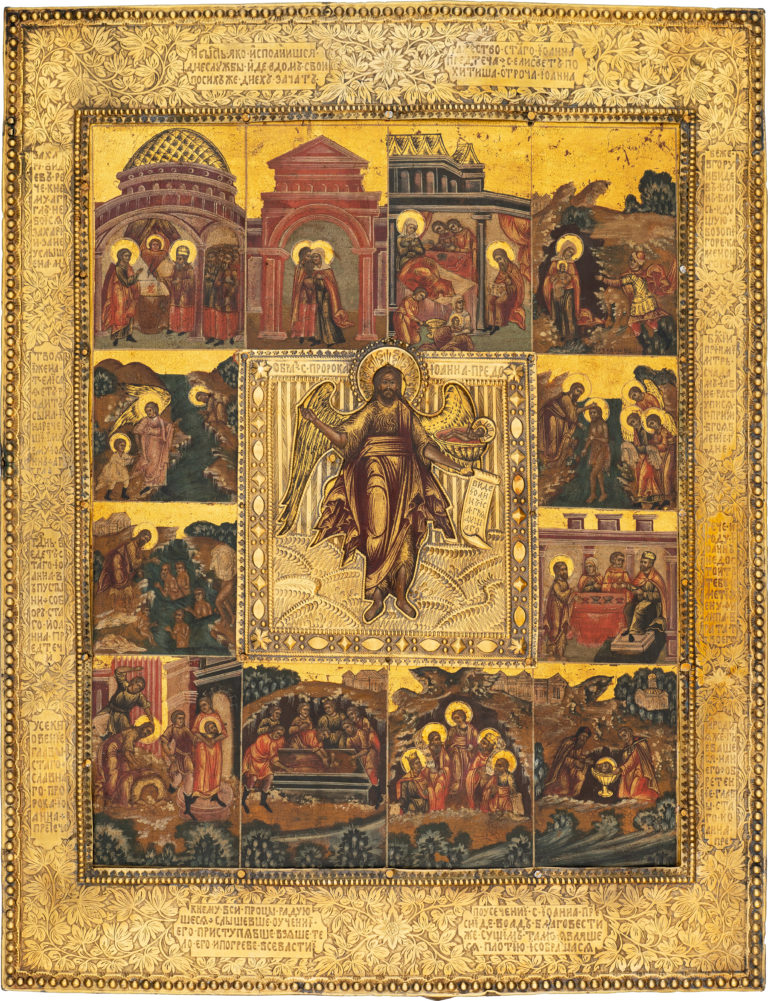

John the Baptist—the Angel of the Desert, with 12 Hagiographical Border Scenes

Antique Russian icon. End of the 18th – early 19th century. Central Russia.

Size: 38 х 29 х 3 cm

Wood (one whole panel), two incut smooth support boards, underlying layer of canvas is not visible, gesso, tempera.

Oklad cover: low-class silver, embossing, engraving.

The author’s paintwork is in an overall good condition. The oklad has partially darkened.

Contact us

John the Baptist—the Angel of the Desert, with 12 Hagiographical Border Scenes

Diagram of the border scenes:

- The Appearance of the Archangel Gabriel to the Prophet Zachariah;

- The Meeting of Zachariah and Elizabeth (The Conception of John the Baptist);

- The Nativity of John the Baptist;

- The Flight of Elizabeth and the Infant John into the Desert;

- The Angel leads the Infant John into the Desert;

- The Theophany (The Baptism of Christ);

- The Baptism of the People of Israel;

- The Condemnation of Herod;

- The Beheading of John the Baptist;

- The Burial of John the Baptist;

- John the Baptist preaches to the dead in Hades;

- The First Discovery of the Head of John the Baptist.

The given piece of hand-painted Orthodox icons of saints depicts John the Baptist (also known as the Forerunner) – the last Old Testament Prophet who preached the coming of Christ into the world and baptized Him in the waters of the Jordan. John is mentioned in all four Gospels, in the Book of Acts, and in early Christian apocrypha. According to the Gospel of Luke (Luke 1:5-24), John was born to the elderly Zachariah and Elizabeth, a couple previously bereft of children. His forthcoming conception was proclaimed by the Archangel Gabriel who appeared to Zachariah during his prayer in the Temple. Disbelieving the prophecy, Zachariah asked the Archangel to prove his words; as a result, the man was made mute and could not speak until the birth of his son. The Gospels do not mention the meeting of Zachariah and Elizabeth. However, since the 13th century, we see the separate scene depicting “The Conception of John the Baptist” in Byzantine art – this composition mimics the Eastern Orthodox iconography of “The Meeting of Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate” (The Conception of the Mother of God). The common fate of two “childless” mothers – Anna and Elizabeth – both of which gave birth to their only child at a great age, is also reflected in the likeness of the two “Nativity” Orthodox Christian icons (of Mary and the Forerunner), where they are shown diagonally, lying on their beds, surrounded by women bearing gifts and servants washing their cherished newborns. Even in the oldest surviving hand-painted icons of the Nativity of John the Baptist, we see the depiction of Zachariah naming his son: he is shown writing on the tablet, after which he resumes the ability to speak. Soon after giving birth, Elizabeth was forced to flee with her infant son into the desert, saving him from King Herod’s warriors sent to kill all the children in Bethlehem who were two years old and under. Elizabeth died forty days after in a cave, and the Infant John was raised in the desert by an Angel until the day he was called by God to preach. The Forerunner preached “baptism of repentance, for the forgiveness of sins” (Mark 1:4, Luke 3:3), seeing that the coming of the Messiah and the Kingdom of Heaven were at hand. Even Christ, being sinless, accepted Baptism from the hands of John, which became an integral part of the Salvation of Mankind. Openly condemning King Herod for his incestuous marriage to Herodiada, the great saint was thrown into prison and later – beheaded. According to the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, after his execution, Saint John preached the coming of Christ to the dead in Hades. Fearing the Resurrection of the Prophet, Herodiada secretly buried his head in one of Herod’s estates, while the body was taken by the Forerunner’s disciples. According to church tradition, the Head of John the Baptist was discovered by two monks in 4th century Jerusalem. This scene, known as the “First Discovery of the Head of John the Baptist,” is the final border scene in the given antique Russian icon.

Hagiographical hand-painted Orthodox icons of Saint John the Baptist have been known since the end of the 14th century and can be characterized by a large number of iconographic variations. The given piece of antique Russian icons of saints has quite a standard selection and number of border scenes. The depiction of the great prophet in the religious icon centerpiece – dressed in camels’ skin and cape, but vested with angels’ wings – belongs to the so-called “Angel of the Desert” iconography that reflects one of the Old Testament prophecies: “I will send by messenger (angel) and he will prepare the way before me” (Malachai 3:1, Mathew 11:10, Mark 1:2, Luke 7:27). In Russian icon art, such hand-painted Orthodox icons of John the Baptist became widespread in the 16th century, often as centerpieces of hagiographical saint icons.

The given antique Russian icon belongs to one of the leading religious icon art movements of the late 18th – early 19th century, which evolved among the Old Believers and yearned to retain Stroganov traditions. Religious icon painters, belonging to the movement, brought back the gold background, the static state of the figures, the graphic base and locality of the colors traditional for that iconography. The fact that this antique Russian icon was held by the Old Believers is attested to not only by the traditional artwork but also by the use of an old panel that could have been kept as a family relic. Such religious icon paintings, the paintwork of which was lost through generations, were often repainted, with the old image being replaced by a new Festive scene or the patron saint of the commissioner. The fact that the artist had to “fill in” the unusually sized panel is clearly evident in the disproportion of the religious icon border scenes: the topmost and lowest tiers are extremely elongated, with too high architectural buildings in the top row and the rough vegetation in the low one.

The oklad is made in the likeness of a frame, completely covering the religious icon borders, with a separate cover plate placed on the centerpiece. The style of the cover allows us to establish the time of its creation – the late 18th – early 19th century. Baroque influence is evident in the floral ornamentation, with the large leaves and pearl-like frames; yet the dry and ordered composition, the symmetry of the graphic work and the cartouches – all attest to a strong classicist influence. This combination of Baroque and Classicist style (along with numerous surviving analogies) enforces our claim as to the cover’s time of origin.