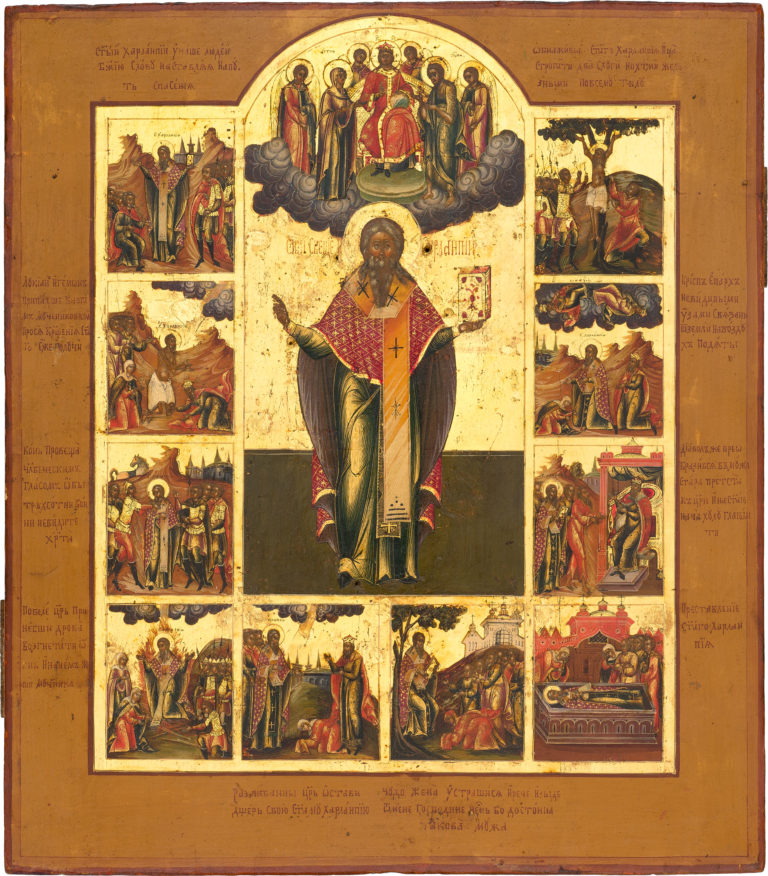

The Martyr Charalambos of Magnesia, with 10 Hagiographical Border Scenes and the Royal Deesis

Antique Russian icon. First third of the 19th century (1820s-1830s). Palekh (?).

Size: 35 х 30.5 х 2.8 cm

Wood (three panels), two incut profiled support boards, absence of an incut centerpiece, underlying layer of canvas not visible, gesso, tempera, gold.

The author’s paintwork is in a very good state. Slight chafing of the paint layer. The background also bears marks from the pinning, which held the devotional crown in place.

The back of the Russian religious icon panel bears an inscription written in ink. Over the topmost support board: Серебра въ ризѣ вѣсу 89 зо 1 че / Сканная Сери[]ка вѣсу 15 зо / Камней францускихъ стр[] – 28мъ камней / 12 надписей Е[] емалевыхъ – 12ть надписей / 1 евангелiе емалевое – 1 евангелiе. Between the support boards: припись и плечики / платья на Святомъ Харлампiи Сканное / золоченье вѣсу неболее 90 зо / чиканку рококо лутчiю. Under the lower support board: 19й 71го.

Contact us

The Martyr Charalambos of Magnesia, with 10 Hagiographical Border Scenes and the Royal Deesis

Diagram of the border scenes:

- Saint Charalambos preaches the Christian faith;

- Two servants torture Saint Charalambos with iron claws;

- The Hegemon of Magnesia Lucian falls down before the feet of the Saint and begs for his forgiveness;

- The Emperor and his courtiers are taken up into the air by a windstorm;

- A Horse speaks with a human voice;

- The Devil, under the guise of an Old Man, comes to the Emperor and falsely accuses St. Charalambos;

- The enraged Emperor orders the burning of the Saint;

- The enraged Emperor leaves his daughter to Charalambos;

- The enraged Emperor gives Charalambos to be mocked by a widow, but she venerates the Saint;

- The Dormition of Saint Charalambos.

This antique Russian icon is a rare representative of hand-painted Orthodox icons of saints. According to the Slavonic tradition, Saint Charalambos was the bishop of the Greek city of Magnesia in Asia Minor. It was here that he was martyred in the reign of Emperor Septimius Severus in the year 202. Having openly professed the Christian Faith (border scene 1), he was brought to the Governor Lucian, who condemned Charalambos to be tortured by iron claws (border scene 2). Seeing the strength and humility, with which the Saint endured the suffering, the Roman warriors embraced the Faith in Christ. On seeing this, the Governor Lucian spat in anger at Charalambos face, but at that moment a miracle happened: the Governor’s head turned backwards. Horrified, Lucian begged the Saint for forgiveness and soon was healed (border scene 3). News of these events reached the Emperor Septimius Severus, who ordered Charalambos to be brought before him at Antioch. The warriors dragged the Saint by a rope tied to his beard. Seeing this brutally, a horse turned to them and with a human voice accused them of cruelty (border scene 5). At the same time, the Devil, under the guise of a Scythian king, came to Septimius Severus and raised false accusations against Charalambos (border scene 6). Believing Satan, the Roman Emperor subjected the Saint to extreme torture, but he remained untouched (border scene 7). Many miraculous events and healing happened at the prayers of the Saint, and many people embraced the Christian faith, including the Emperor’s daughter Galina. One of the Emperor’s courtiers, Crispus, persuaded Septimius that Charalambos was a sorcerer, not a Christian, after which both began to mock God; but – to the terror of everyone around – they were taken by an unseen force unto the sky (border scene 4). Returning back to the ground by the prayers of Charalambos, the Emperor and his courtier immediately renewed the torture of the Saint. Trying to aid the Saint, the princess Galina began to crush the heathen idols in the temple, which enraged the Emperor even more, and he renounced his daughter (border scene 8). Septimius Severus decided to give the Saint to be mocked by a certain widow. But when Charalambos was brought to her house, he turned one of the pillars into a tree – and the widow immediately embraced the Faith in Christ and bent her knees before the martyr (border scene 9). Then the Emperor chose the last measure and ordered for the saint to be beheaded. Charalambos fervently prayed before his execution – and the Lord with His angels came from the skies to personally take the martyr’s soul to Heaven.

The Eastern Orthodox iconography of the given antique Russian icon, as well as the selection of the border scenes, is typical for the Imperial era. According to iconographer’s manuals, Saint Charalambos was to be depicted as an elder in liturgical vestments (a green sticharion, red phelonion, and an omophorion), with a Gospel in his left hand, with his right hand in a two-finger sing of the cross blessing gesture. In the Byzantine tradition, religious icon paintings and depictions of Saint Charalambos were known from ancient times but still were quite rare. In the Russian Eastern Orthodox iconography tradition, the saint’s icons and depictions become widespread in the Imperial period, predominantly among the Old Believers. Since then, Saint Charalambos was depicted in religious icon paintings as the protector from unexpected death and death without penance – this was especially central for Old Believers, who were constantly under severe persecution from the state. In Russian folk tradition, Saint Charalambos is seen as the healer from ailments, the protector of livestock and crops, the saint who could improve the wealth of a family and free it from hunger. His Feast is celebrated on February 23rd (February 10th according to the Old Calendar).

Stylistic traits of the given antique Russian icon allow us to establish its origins in the iconographic workshops of the Vladimir region, which retained the traditional religious icon painting style and the orientation on 17th-century Russian icon art. The intricate execution of the faces, the solid graphic baseline, the reduced color scheme (built ochres, pinkish-reds, lilacs, and greens), the colorful, ornamented buildings, and featherlike mountains give this beautiful hand-painted antique icon a highly festive character. This piece of religious icon paintings finds close analogies among other Eastern Orthodox icons of Palekh masters of the first third of the 19th century.

The inscription on the reverse of the religious icon panel is of special interest. It provides detailed information on the now lost oklad cover (traits of its presence can be seen on the ribs and around the halo of Saint Charalambos). It was probably made in the middle of the 19th century, since the phrase «чиканку рококо лутчiю» (misspelled Russian for “best rococo embossing”) attests to the fact that the silversmith was looking towards baroque art, which was popular during the “historicism” movement of the 1840s-1850s.

According to the inscription on the given Russian Orthodox icon, a lavish embossed oklad cover was decorated with 28 French-cut gems and 12 enamel inscribed medallions. The figure of Saint Charalambos was covered with gilded filigree vestments. Such an oklad cover bears witness to the fact that this particular hand-painted antique icon was held in the highest possible reverence and veneration.