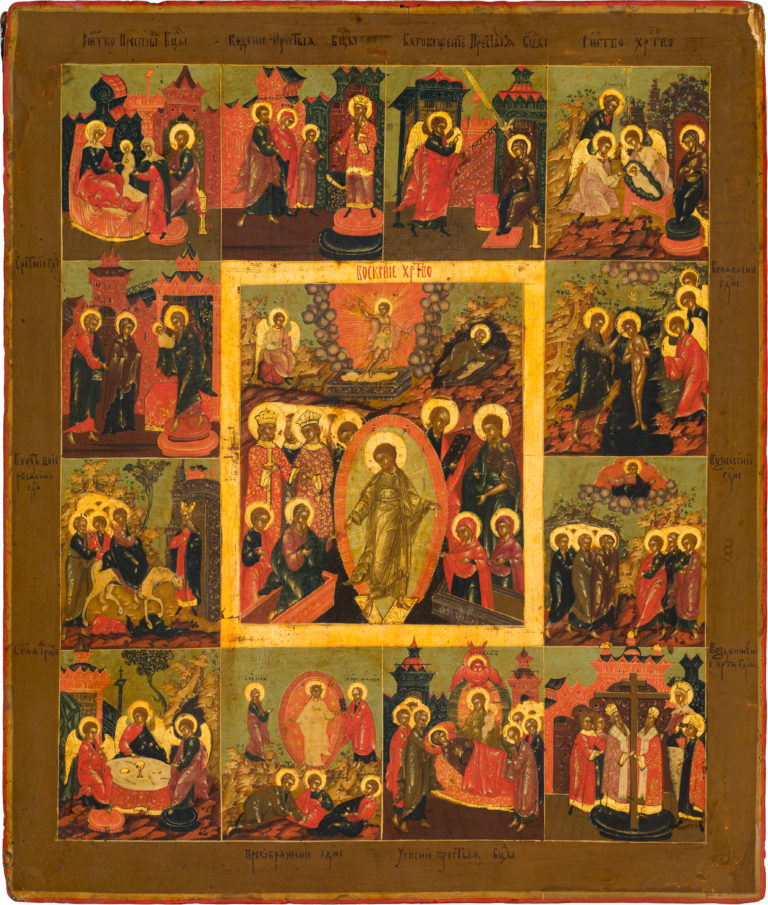

The Resurrection—the Descent into Hell, with Church Feasts in 12 Border Scenes

Second quarter of the 19th century. Palekh.

Size: 36 х 31 х 3 cm

Wood (one whole panel), two incut support planks, absence of an incut centerpiece, underlying layer of canvas not visible, gesso, tempera.

The author’s paintwork is very well preserved. Small fallouts of gesso on the borders, slight chafing of the paint, few fragments of darkened varnish (olifa) that were missed at restoration.

Contact us

The Resurrection—the Descent into Hell, with Church Feasts in 12 Border Scenes

Diagram of the border scenes:

- The Nativity of the Mother of God;

- The Entrance of the Mother of God into the Temple;

- The Annunciation;

- The Nativity of Christ;

- Candlemas (The Meeting of Christ in the Temple);

- Theophany (The Baptism of Christ);

- The Entrance into Jerusalem;

- The Ascension;

- The Old Testament Trinity;

- The Transfiguration;

- The Dormition of the Mother of God;

- The Elevation of the Holy Cross.

Eastern Orthodox icons depicting the major Feast cycle of the Liturgical year were known as polnitsy (basically “full” or “full-cycle” religious icons), and were among the beloved themes of Palekh iconographers. Such small hand-painted icons were usually commissioned for homes and private prayer-corners.

The Resurrection – The Descent into Hell scene is compositionally split into two rows with two centers. The top row is occupied by the scene of the Rising from the Tomb – an Eastern Orthodox iconography formed directly under Western influence, with an angel in white robes sitting on the stone on the right and the scene of “Peter at the Empty Tomb” on the left. The lower row bears the traditional scene of the Harrowing of Hades. Christ is depicted in the shining mandorla, stepping over the fallen gates of Hell. To the left, we see Adam rising from his tomb and being held by Christ. Eve is depicted in a similar fashion to the right of Jesus, wearing a red maphorion and backed by a pious woman. John the Baptist stands behind Adam, with the kings, prophets, and pious men of the Old Testament. Other iconographic details, sometimes found in the Resurrection, are absent from this piece of antique Russian icons.

Despite the fact that the given hand-painted icon instantly evokes the highly-recognizable style of the Vladimir village of Palekh – one of the greatest religious icon painting centers of the Russian Empire – it bears a unique and atypical iconographic scheme. The composition of the centerpiece differs from other known examples, while the order of Feasts in the border scenes does not follow the liturgical calendar. Unlike other Palekh religious icon paintings, this one has the border scene with the Old Testament Trinity (a Feast celebrated 50 days after Pascha) not in the topmost center, which would be typical, but in the lower left corner, following the Ascension (celebrated 40 days after Pascha). The Transfiguration (celebrated on August 19th) is also taken out of the linear Gospel narrative and placed in accordance with the Church calendar, directly before the Dormition of the Mother of God (August 28th). Nevertheless, famous religious icons by Palekh masters in various state and private collections attest to the fact that such simplified iconographic deviations were widespread.

Palekh – which underwent its formation as one of the largest iconographic centers of the Empire in the second half of the 18th century – uniquely combined the strict adherence to the canon and tradition with fervent appreciation of later-day Yaroslavl and Stroganov religious icon art. The love for Yaroslavl and Stroganov traditions is especially evident in the bright color pallet and miniature details of Palekh hand-painted icons. While the detailed execution of the faces, vestments, and crystal-like mountains covered with extravagant vegetation reflects the golden age of Palekh religious icon art – the rich, yet slightly subdued color pallet (with numerous shades of brown and dark green), the deformation of body proportions, enlargement of the figures, which occupy almost the entire space of the centerpiece and border-scenes, and the lack of a clear composition all indicate that the published antique Russian icon was painted in the second quarter or middle of the 19th century.