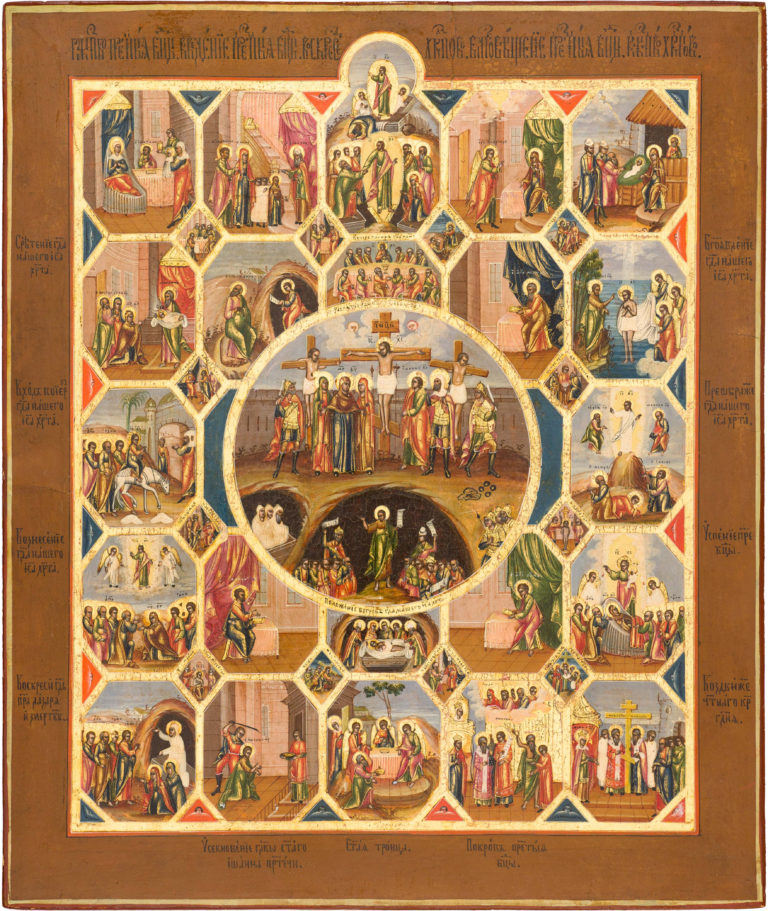

The Crucifixion, with the Passions of Christ and Selected Church Feasts

Antique Russian icon. Third quarter of the 19th century. Palekh.

Size: 44.5 х 37 х 2.7 cm

Wood (two panels), two incut support boards, absence of the incut centerpiece, underlying layer of canvas is not visible, gesso, tempera.

The author’s paintwork is very well preserved with only slight chafing on the religious icon borders.

Contact us

The Crucifixion, with the Passions of Christ and Selected Church Feasts

Hand-painted Orthodox icons of the Crucifixion, which included the great Church Feasts and the Passion narrative, became widespread in later period Russian icon art. The centerpiece of such religious icon paintings usually bears the depictions of the Resurrection – the Harrowing of Hades, but in this case, it is replaced by the Crucifixion, which makes a greater emphasis on the Passions of Christ. The compositional scheme is indeed complex and original, with the centerpiece being enclosed in a circle, along the perimeter of which, we see four rows of diamond-shaped, many-angular, and triangular border scenes. Such hand-painted icons are usually found in religious icon art of Palekh masters, in whose workshops this iconographic scheme was finally shaped. The traditional execution and stylistic traits of the given antique Russian icon allow the dating of the piece to be placed at the third quarter of the 19th century.

The iconography of the religious icon centerpiece belongs to the highly developed type of the Crucifixion, with the composition including two crucified thieves, the Myrrh-bearing women, the Mother of God, Longinus the Centurion, and the Roman warriors. The scene is supplemented by a rather rare depiction of John the Baptist preaching the coming of Christ in Hell, so that “all those who have faith in Him will be saved, and those that do not – be condemned.” The central axis brings together the main events linked with the Passions and Resurrection narrative – the culmination of God’s Salvation of Mankind. The life of suffering, ending with the Death on the Cross, brings Christ to the glory of the Resurrection and the Harrowing of Hades. Christ himself attested to this at the Last Supper, “Now the Son of Man is glorified and God is glorified in him” (John 13:31) – that is why the Last Supper scene is depicted directly below the Harrowing of Hades. The centerpiece composition includes the images of the Four Evangelists (John the Theologian, Matthew, Mark, and Luke) depicted at each religious icon corner, as the four Pillars of the Church.

The Passion cycle unravels in the diamond-shaped border scenes that take their place between the centerpiece and the Great Feasts. It includes fourteen border scenes (the Washing of the Feet; Judas taking the 30 pieces of silver; the Prayer in Gethsemane; the Betrayal of Judas and Arrest of Christ; Christ before Pilate; the Denial of Peter; Christ before Caiaphas; the Flagellation of Christ; the Crown of Thorns; the Carrying of the Cross; Joseph of Arimathea asking Pilate for the Body of Christ; the Taking Down from the Cross), two of which (The Last Supper and the Entombment of Christ) are brought out to the central axis and are expanded in size, thus emphasizing the themes of Passion and the Resurrection.

The exterior cycle of religious icon border scenes includes the Twelve Great and Minor Feasts of the Church: the Nativity of the Mother of God; the Entrance of the Mother of God into the Temple; Candlemas (the Meeting of Christ in the Temple); the Theophany (Baptism of Christ); the Entrance into Jerusalem; the Transfiguration; the Ascension; the Dormition of the Mother of God; the Raising of Lazarus; the Beheading of John the Baptist; the Old Testament Trinity; the Pokrov of the Mother of God; the Elevation of the Holy Cross.

Hand-painted Orthodox icons of the Feasts were especially venerated by the faithful, which is explained by their practical use in the household – a single panel contains the main Feasts of the Liturgical year, which makes the religious icon a kind of the miniature iconostasis. In folk culture, such pieces were seen as the reflection of the agricultural year with all of its cycles and events. That is why these holy icons were painted for commissioners hailing from all social classes, and iconographers were willing to accept all orders.