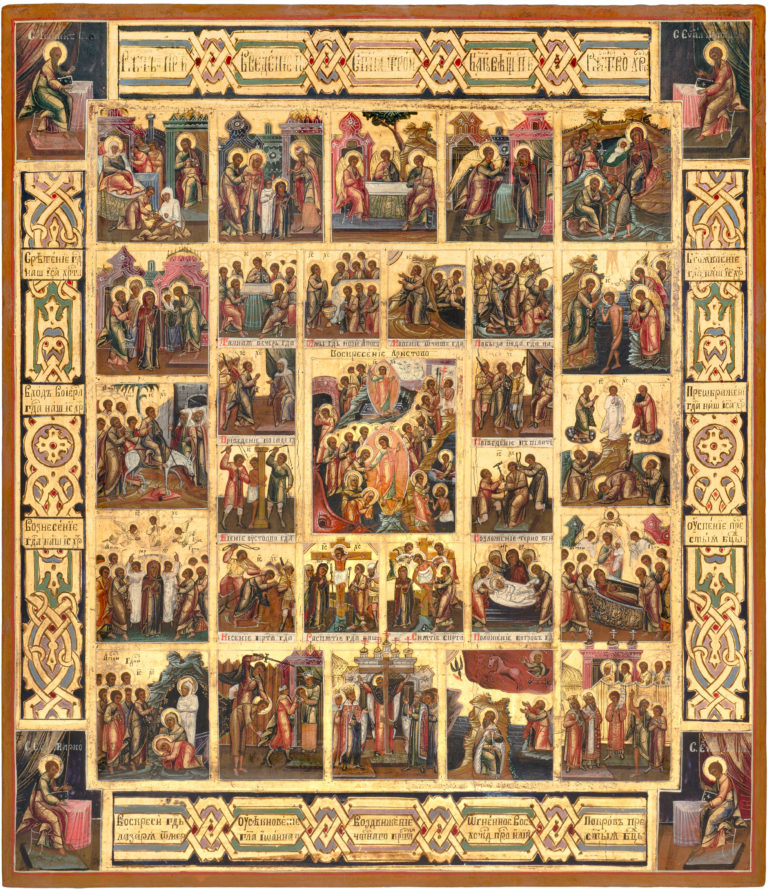

The Resurrection—the Descent into Hell, with the Passions of Christ, Church Feasts, and the Four Evangelists in 28 Border Scenes

Icon: End of the 19th century. Icon-painting villages of the Vladimir region (Kholuy or Mstyora).

Size: 36 х 31 х 2.5 cm

Wood (four panels), two incut support boards (now lost), a shallow incut centerpiece, underlying layer of canvas not visible, gesso, tempera.

The author’s paintwork is in good condition.

Contact us

The Resurrection—the Descent into Hell, with the Passions of Christ, Church Feasts, and the Four Evangelists in 28 Border Scenes

Diagram of the border scenes:

The Feast cycle:

- The Nativity of the Mother of God;

- The Entrance of the Mother of God into the Temple;

- The Old Testament Trinity;

- The Annunciation;

- The Nativity of Christ;

- Candlemas (The Meeting of Christ in the Temple);

- The Theophany (The Baptism of Christ);

- The Entrance into Jerusalem;

- The Transfiguration;

- The Ascension;

- The Dormition of the Mother of God;

- The Raising of Lazarus;

- The Beheading of John the Baptist;

- The Elevation of the Holy Cross;

- The Fiery Ascent of the Prophet Elias;

- The Pokrov (Feast of the Protective Veil of the Mother of God).

The Passion cycle:

- The Last Supper;

- The Washing of the Feet;

- The Prayer in Gethsemane;

- The Betrayal of Judas and the Arrest of Christ;

- The Bringing of Christ before Caiaphas;

- Christ before Pilate;

- The Flagellation of Christ;

- The Crown of Thorns;

- The Carrying of the Cross;

- The Crucifixion;

- The Taking Down from the Cross;

- The Entombment of Christ.

- The Evangelist John the Theologian;

- The Evangelist Matthew;

- The Evangelist Mark;

- The Evangelist Luke.

The given antique Russian icon is dedicated to the Resurrection – the Harrowing of Hades, with the Passion cycle – a complex iconographic composition that is quite traditional for the Imperial period. This religious icon composition includes two Resurrection scenes – the Rising from the Tomb and the Harrowing of Hades, connected by a diagonal processional line of the Pious, marching from Hell to the Kingdom of Heaven, and supplemented by other scenes that either took place before or after the Resurrection (in this case only one – the Revelation of Christ to the Apostles on the Sea of Galilee). The centerpiece of the hand-painted icon does not really stand out alongside the exterior frame of Festive border scenes and seems to get lost among the depictions of the Passion narrative. Besides, the religious icon composition of the scenes is dependent on a wide range of sources – from the traditional medieval iconographic samples to Western European portrayals. The narrative of the upper tier of Feasts, which traditionally begins with the Nativity of the Mother of God, is chronologically broken by the depiction of the Old Testament Trinity placed along the central axis. The lower tier includes four minor Feasts that were typically included into similar Eastern Orthodox Church icons since Palekh artists devised this complex composition in the early 19th century. These are the Beheading of John the Baptist, the Elevation of the Holy Cross, the Fiery Ascent of the Prophet Elias, and the Pokrov of the Mother of God. In the corners of this antique Russian icon, we see the depictions of the Four Evangelists: John the Theologian, Matthew, Mark, and Luke.

The simple character of the artwork attests to the fact that such hand-painted Orthodox icons were indeed produced on a mass scale. They were mainly painted in the Russian icon-painting villages of the Vladimir region, Mstyora and Kholuy, which had several workshops specializing in the mass production of religious icons. The conventionalism of their execution, the highly-standardized painting style, and the use of popular iconographic schemes in both centers make the differentiation between them difficult. However, pre-revolutionary studies have left us detailed descriptions of the religious icon production popular at that time. The process was broken into almost 40 stages (each taken on by a separate Russian icon master or artisan), and the overall amount of hand-painted icons produced yearly in Kholuy and Mstyora came up to shocking numbers – up to 2,500,000 a year. The manner of religious icon painting clearly reflects late 19th-century art, when iconographers began to imitate the ornamentation of precious oklad covers they saw on higher level Eastern Orthodox Church icons. The interwoven ornaments that are clearly seen in this antique icon were taken from the decorative motifs of the 17th-century Russian architectural depictions.