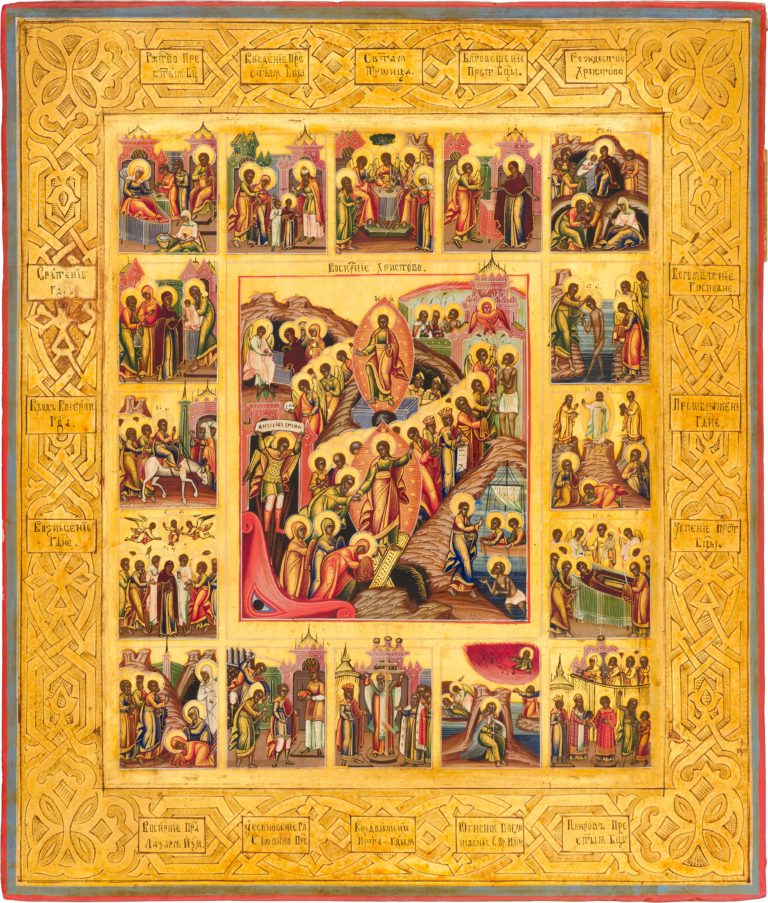

The Resurrection—the Descent into Hell, with Church Feasts in 16 Border Scenes

Antique Russian icon. End of the 19th century. Mstyora.

Size: 31 х 26.5 х 2.5 cm

Wood (possibly cypress), one whole panel, two incut smooth support boards, a shallow incut centerpiece, the underlying layer of canvas is not visible, tempera, gold, embossing on the gesso.

The author’s paintwork is in a very good state. Slight chafing of the gold on the borders.

Contact us

The Resurrection—the Descent into Hell, with Church Feasts in 16 Border Scenes

Diagram of the border scenes:

- The Nativity of the Mother of God;

- The Entrance of the Mother of God into the Temple;

- The Old Testament Trinity;

- The Annunciation;

- The Nativity of Christ;

- Candlemas (The Meeting of Christ in the Temple);

- Theophany (The Baptism of Christ);

- The Entrance into Jerusalem;

- The Transfiguration;

- The Ascension;

- The Dormition of the Mother of God;

- The Raising of Lazarus;

- The Beheading of John the Baptist;

- The Elevation of the Holy Cross;

- The Fiery Ascent of the Prophet Elias;

- The Pokrov (Feast of the Protective Veil of the Mother of God).

Eastern Orthodox icons bearing the depictions of the liturgical Feast cycle were known among the religious icon painters of the Imperial era as “polnitsy” (basically – “Full-cycle icons”). Such complex iconographic compositions allowed one to bring together on a single panel all main events of the Gospel narrative, which made such hand-painted Orthodox icons especially popular among all social ranks in Russia. These religious icon paintings were often commissioned by churches as grand ‘temple icons’ while smaller ones were placed on the analoion for veneration during Sunday services. Besides, they were also commissioned for private prayer. The iconographic composition of such Eastern Orthodox Church icons evolved in the late 18th century in Palekh and became increasingly popular in Russian icon art during the next century. The centerpiece of the given hand-painted icon bears the detailed image of Christ’s Resurrection. Two different Resurrection scenes are depicted along a single vertical line: the historical event – the Rising from the Tomb – is shown alongside the symbolic representation – the Harrowing of Hades, with both religious icon scenes being bound together by the diagonal line of the Pious marching from Hell into Heaven. The central scene is flanked by events that are either predated or followed the Resurrection. In the top left corner, we see the Angel before the Myrrh-bearing women; in the lower right corner – the Revelation of Christ to the Apostles on the Sea of Galilee. The surrounding border scenes are dedicated to the Twelve Great Feasts (the Annunciation; the Entrance of the Mother of God into the Temple; the Elevation of the Holy Cross; the Theophany; the Transfiguration; the Nativity of the Mother of God; the Nativity of Christ; Candlemas; the Dormition of the Mother of God; the Entrance into Jerusalem; the Ascension; the Holy Trinity (Pentecost)), as well as to the Minor Feasts (the Beheading of John the Baptist, the Pokrov of the Mother of God) along with two other scenes – the Raising of Lazarus (the main symbol of the Resurrection of the Dead) and the Fiery Ascent of the Prophet Elias – the central Old Testament indication of mankind’s ability to regain the Kingdom of Heaven. The Prophet Elias and the Prophet Enoch are considered the only two men who were able to reach heaven before the Resurrection of Christ; that is why they are depicted standing at the Gates of Heaven, welcoming those pious men and women who were delivered by Jesus from the mouth of Hell.

Stylistic traits of this small antique Russian icon, especially the decorative yet simplified religious icon painting style, the thick, enamel-like paint layers, the small, graphic mountains, and the slightly dry gold hatching along with the artists clear desire to follow the old iconographic tradition – all testify to the fact that it was painted by a Mstyora iconographer at the end of the 19th century. Religious icon art of that period is noted for the gold etching of the background and borders, which created the illusion of an expensive oklad cover being placed on the hand-painted icon, while the ornamentation itself was distinguished by great diversity and subtlety of execution. The borders of the Feasts are covered with openwork, geometric patterns, which are reminiscent of engraved boards. The desire to recreate the 17th-century Russian architectural motifs is quite typical for the so-called “neo-Russian” style of the 1860s-1890s, popular among religious icon painters of the Vladimir region.