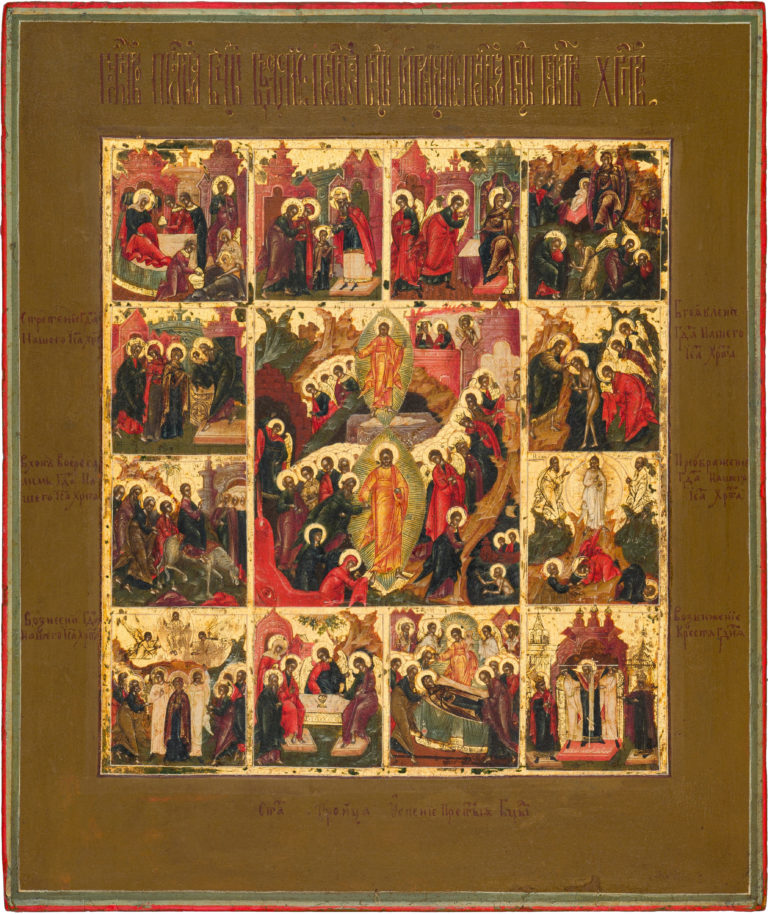

The Resurrection—the Descent into Hell, with Church Feasts in 12 Border Scenes

Antique Russian icon. First third of the 19th century. Palekh.

Size: 31 х 26 х 2 cm

Wood (one whole panel), two incut profiled support boards, a shallow incut centerpiece, underlying layer of canvas, gesso, tempera, gold.

The author’s paintwork is in a very good state with only slight chafing and several fallouts of paintwork in places. On the rib of the panel (on the right), there is an ink inscription «праз/ики» (Russian for “Feasts”). On the backside of the panel, above the top support board, there is another inscription – in pencil – with the Russian word “ризу” (“Riza cover”). Such inscriptions are common for the 19th-century Russian icon paintings and were usually placed by the craftsman who took a religious icon to make an oklad (or riza) cover. The nail holes on the edges of the panel indicate that the oklad cover was indeed devised and placed on this antique icon.

Contact us

The Resurrection—the Descent into Hell, with Church Feasts in 12 Border Scenes

Diagram of the border scenes:

- The Nativity of the Mother of God;

- The Entrance of the Mother of God into the Temple;

- The Annunciation;

- The Nativity of Christ;

- Candlemas (The Meeting of Christ in the Temple);

- The Theophany (The Baptism of Christ);

- The Entrance into Jerusalem;

- The Transfiguration;

- The Ascension;

- The Old Testament Trinity;

- The Dormition of the Mother of God;

- The Elevation of the Holy Cross.

Eastern Orthodox icons of the Resurrection – The Harrowing of Hades surrounded by the Twelve Great Feasts were widespread in the 19th century. Large hand-painted icons were commissioned by churches as ‘temple icons,’ while smaller ones were placed on the analoion during Sunday services. Small religious icon paintings with such scenes could also be found in homes. These holy icons gained popularity because of their all-inclusive composition that brought together the main Feasts of the Liturgical year with the main Feast – Pascha (The Resurrection of Christ) – being placed in the center.

The border scene cycle begins with the Nativity of the Mother of God – the first major Feast celebrated on September 8th of the Julian calendar (the Orthodox Church year begins on September 1st). Then the border scenes follow the historical order, which is related to the fact that many of the Feasts are moveable and don’t have a fixed day, being dependent on the date of Pascha. Despite the fact that the liturgical year ends with the Feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God (August 28th of the Julian calendar), the last border scene of this antique Russian icon is occupied by the Elevation of the Holy Cross (September 27th of the Julian calendar). Thus, one religious icon contains the entire Festive cycle revolving around the main Feast – the Feast of Pascha.

The central event depicted in this hand-painted icon is represented in great detail. According to the tradition, which appeared in the 16th century and became quite popular in the Imperial era, Christ is depicted twice. In the upper part of the composition, Christ is represented Rising from the Tomb, with His hand in a blessing gesture. Simultaneously, Christ is shown in the Harrowing of Hades scene, raising Adam by the arm and taking him out of the mouth of Hell. The line of those saved from Hell is led by the Good Thief – Rach – who is also depicted twice: standing before the gates of Heaven and in Heaven itself, conversing with Elijah and Enoch. Although iconographers often included other scenes into the Resurrection narrative, which either took place before or after the event, in the given antique icon, only one such scene is shown: the Revelation of Christ to the Apostles on the Sea of Galilee. According to the Gospel (John 21), Christ was first recognized by the apostle John, while Peter, who was naked, clad himself into his cloak and jumped into the sea swimming towards the Lord.

The noble and subtle color scheme (with its green and brown tones) enriched by crimson and cherry tones, dark grass-green borders, the exquisite miniature painting, the highly-recognizable architectural staffage with its white ornamentation, and crystal-like mountains with small light covered platforms – all attest to the fact that the given antique Russian icon was painted in Palekh. Despite the wonderful artistry, the complexity of the composition and the darkened color pallet indicate that this hand-painted icon was created in the 1820s or 1830s, not earlier.